Urban ecosystem services justice

14 May 2020As ecosystem services are becoming more and more important not least in urban planning, there is an urgent need to critically think about “Weaving notions of justice into urban ecosystem services research and practice“. Justice is a blind spot this article in Environmental Science & Policy by ICTA researchers Johannes Langemeyer and James Connolly provides theoretical entry points and examples to address this, by developing an ecosystem service justice model from an urban perspective.

The article claims that for building an urban ecosystem services justice model, we need to overcome some core limitations embedded in the ecological and economic legacy of the ecosystem services concept. First, the classical (rural) framing of stocks of natural capital that deliver benefits to people oversimplifies the deeply interconnected character of social-ecological systems in the co-production of benefits for human wellbeing, for instance in the production of food. Secondly, the predominance of economic understandings of values guiding ecosystem services assessments, leads to an overemphasis toward Pareto-optimal solutions, which by definition do not account for distribute effects of ecosystem services.

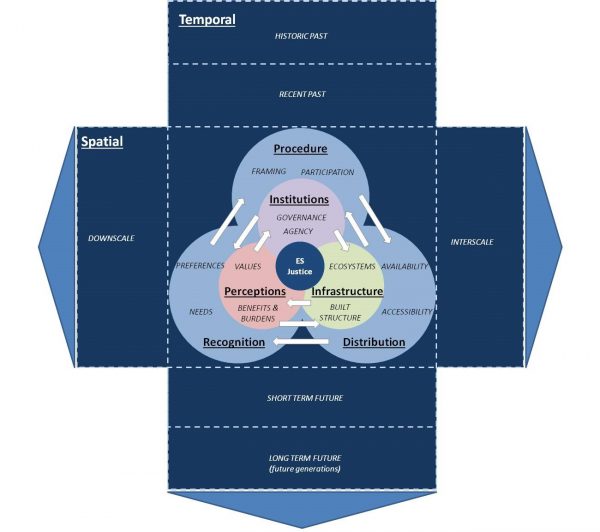

The urban environmental justice literature provides entry points to overcome these critical limitations in ecosystem services models; taken together with advanced research on urban ecosystem services, a new model for urban ecosystem services justice can emerge. The model presented here considers three relevant filters (Andersson et al., 2019), namely infrastructure, institutions and people’s perceptions, that can either facilitate or hamper the flow of ecosystem service benefits, which are related to the three core dimensions of urban environmental justice, recognition, procedural and distribution justice. While the societal distribution of ecosystem services benefits requires careful assessments, ecosystem services justice also requires to consider people’s multiple values and needs, as well as procedural justice in form of participation but also – and as importantly – by acknowledging that ecosystem services is not a neutral concept and consequently there is the necessity for a critical understanding of the framing of ecosystem service-based decision making.

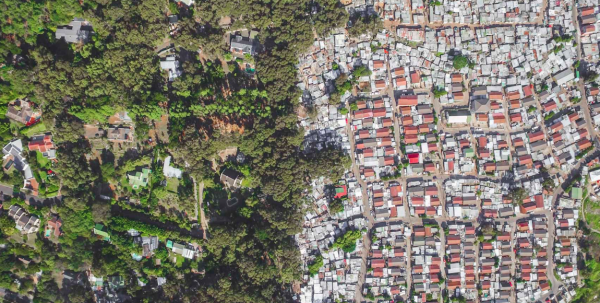

In addition, the authors highlight two core frontiers to make urban ecosystem services justice happen: First, a stronger integration of spatial justice, considering both the benefits and burdens from ecosystem service planning outcomes at a super-local scale as well as through inter-scalar teleconnections affecting people globally. Second, urban ecosystem services justice needs to incorporate temporal justice, both from a historical perspective of injustices as well as mid and longterm temporal dimensions of ecosystem services justice that are related to urban resilience and long-term sustainability.